How a Car Radiator Works and Why It Matters

Learn how a car radiator works, why system pressure matters, and how designs evolved from early honeycomb models to modern cooling systems. Read more.

A radiator is, in simple terms, the engine’s cooling partner. Every time fuel burns inside the engine, heat is produced. If that heat isn’t controlled, the engine can overheat quickly. The radiator exists to prevent exactly that.

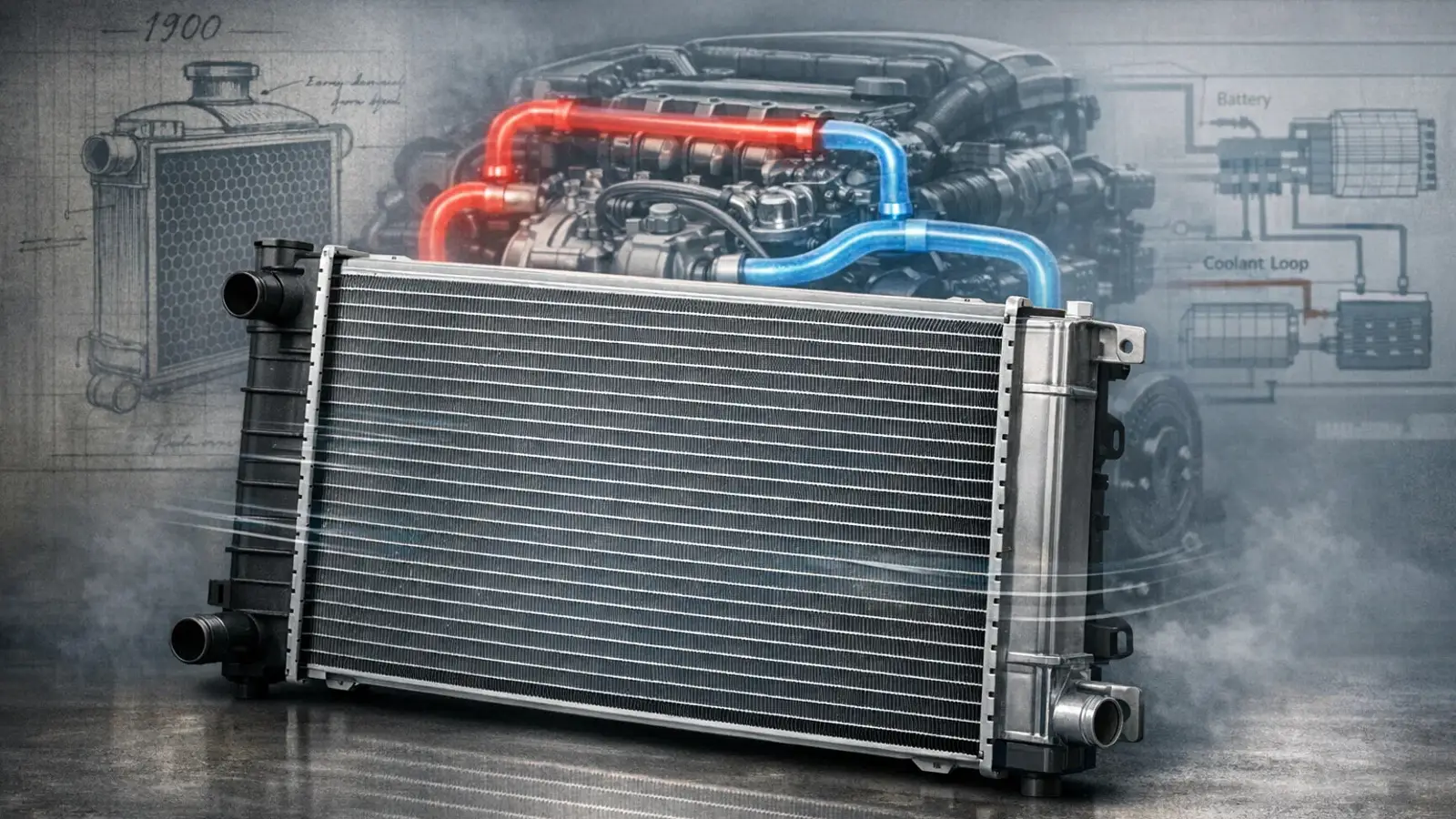

The process is easy to understand. Coolant flows through the engine and absorbs excess heat. It then travels into the radiator, where it moves through many thin tubes surrounded by metal fins. Air passes across those fins—either because the car is moving or because a fan pushes air through at low speeds. The air carries heat away, the coolant cools down, and the cycle begins again.

A thermostat plays an important role in this loop. When the engine is cold, coolant circulates in a small circuit and bypasses the radiator so the engine can warm up faster. Once operating temperature is reached, the path through the radiator opens and full cooling begins.

Pressure inside the cooling system is not accidental. Running under pressure raises the coolant’s boiling point. A commonly cited figure is about 3°F per 1 psi of added pressure. That’s why the radiator cap matters—it maintains the specified pressure and uses a spring-loaded valve to release excess pressure when needed, helping keep the system stable under load.

Although it looks simple from the outside, a radiator is carefully engineered inside. The core contains numerous tubes and thin fins that increase the surface area for heat transfer. Modern designs often combine an aluminum core with plastic side tanks, balancing weight and efficiency.

Radiator development dates back to the late 19th century. A tubular radiator is associated with 1897, and by 1900 the “honeycomb” radiator appeared on the Mercedes 35 PS. That design used thousands of small channels, dramatically increasing heat-transfer surface and improving cooling performance.

There have been alternatives to liquid cooling. Air-cooled engines transfer heat directly to the air through finned cylinders and heads, supported by airflow and, in some cases, a fan. Vehicles also use additional heat exchangers, such as the heater core that draws warmth from the engine to heat the cabin.

In modern electric vehicles, thermal management remains essential. Battery packs, power electronics, and electric motors all require temperature control. Recent overviews describe a shift toward more integrated thermal systems with multiple cooling loops. The technology evolves, but the core idea remains the same: heat must be moved away efficiently and under control.

In the end, the radiator is more than a box at the front of the car. It is a central part of a system designed to keep temperatures steady, protect components, and ensure reliable operation in everyday driving conditions.

Allen Garwin

2026, Feb 22 16:26